Interview de Ian Mackinnon

Ian Mackinnon est producteur d’animation en stop-motion. Avec Peter Saunders, ils ont créé leur Studio Mackinnon & Saunders dans les années 90 à Manchester. Ils fabriquent des figurines et produisent leurs propres animations, travaillant avec les plus grands réalisateurs tels que Tim Burton (depuis Mars Attacks!), Wes Anderson (Fantastic Mr. Fox et L’Ile aux Chiens) et Guillermo del Toro (Pinocchio). Découvrez la magie qui se cache derrière la réalisation des Noces Funèbres et de Frankenweenie :

Quand et comment as-tu découvert la stop-motion?

J’ai toujours été intéressé par les marionnettes, surtout les marionnettes à gaine comme dans Sesame Street et Le Muppet Show. En grandissant, je me disais que ce serait génial de travailler dans ce milieu. J’ai toujours entendu parler de la stop-motion parce qu’il y a beaucoup de programmes télévisés pour enfants en stop-motion réalisés au Royaume-Uni que je regardais : The Clangers, Trumpton, Camberwick Green…

J’ai découvert le travail de Ray Harryhausen avec ses films, mais la technique qu’il utilisait était un mystère pour moi. Je comprenais comment fonctionnait Kermit la Grenouille, mais il y avait très peu de livres dans nos bibliothèques à l’époque, pas d’Internet et pas de vidéo making-of pour découvrir comment était faite la stop-motion, donc c’était inaccessible pour moi. Je n’avais aucune idée de comment c’était fait et je ne réalisais même pas que ça se passait à moins de 30km de chez moi à Manchester. Peter Saunders, mon associé actuel, m’a aidé à obtenir mon premier job juste après mes études. J’ai travaillé pour Gerry Anderson, un producteur TV qui a notamment produit Les Sentinelles de l’Air et Capitaine Scarlet. C’étaient des marionnettes qui vivaient des aventures extraordinaires en séries. Travailler pour Gerry Anderson m’a fait découvrir le monde de la création d’accessoires pour le cinéma. Quand je suis retourné à Manchester, j’ai travaillé avec Peter Saunders dans les Studios Cosgrove Hall en produisant des séries en stop-motion telles que Le Vent dans les Saules. J’ai passé des années à me former dans les studios et à gravir les échelons étape par étape.

Comment vous vous divisez le travail avec Peter Saunders?

Nous sommes avant tout des fabricants de figurines mais nous sommes également producteurs maintenant. Je passe plus de temps sur le design et les sculptures, essayant de comprendre ce que les réalisateurs et producteurs veulent comme style pour leurs personnages. Peter vient du monde de l’ingénierie. Il a développé des systèmes innovants de têtes et visages mécaniques. Il a commencé avec Jim Henson sur le film Dark Crystal. Il a travaillé sur la miniaturisation d’animatroniques pour les têtes des personnages et a ensuite appliqué cette technique à la stop-motion. C’est comme ça que nous nous partageons le travail mais depuis quelques temps, avec l’entreprise que nous avons créée ensemble, nous produisons également. Nous avons produit des séries TV pour enfants, des publicités, des court-métrages et toutes les séquences en stop-motion de Beetlejuice Beetlejuice dans notre studio. Nous avons plusieurs cordes à notre arc.

Comment s’est passée votre première collaboration avec Tim Burton en 1996? Comment a-t-elle évolué depuis?

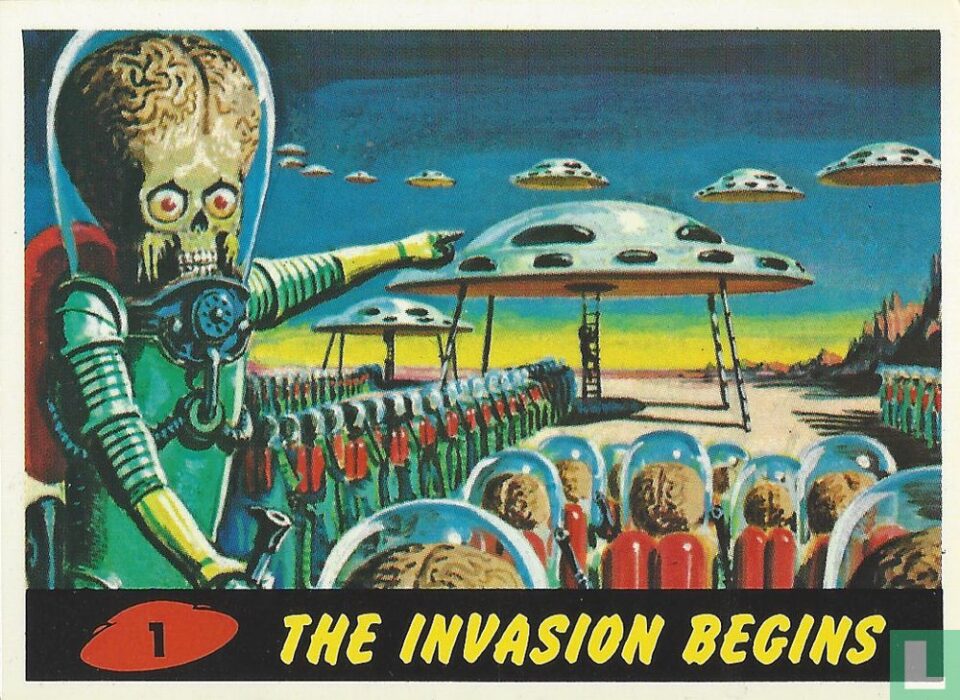

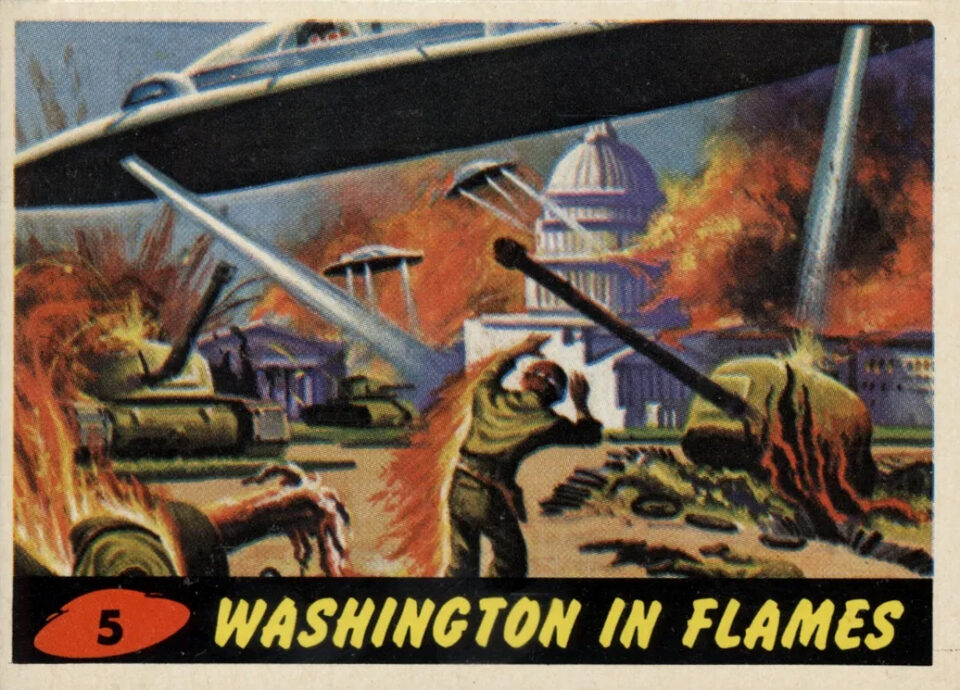

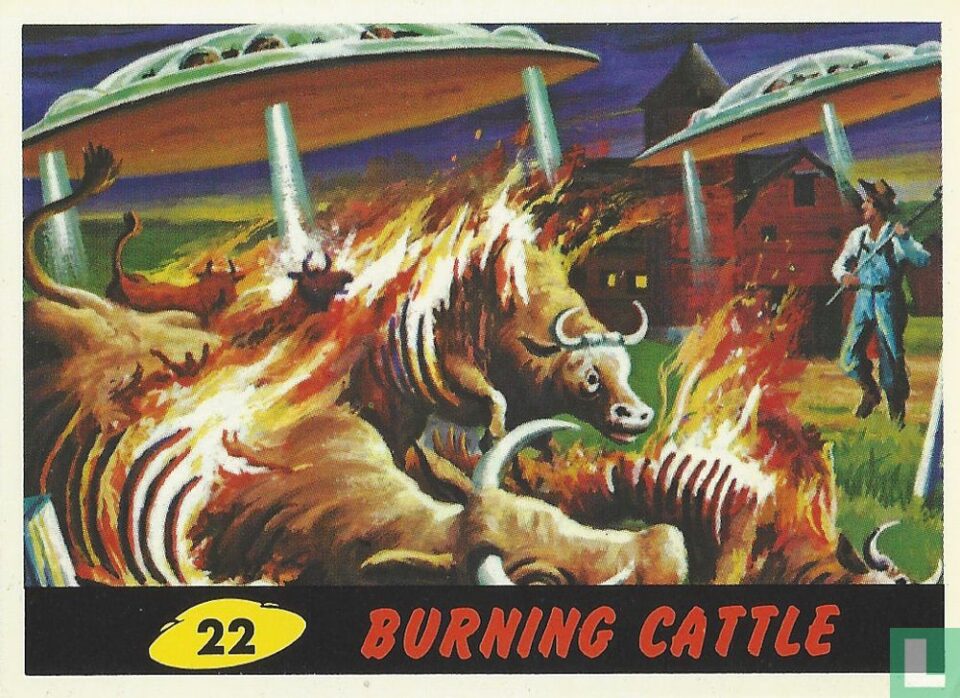

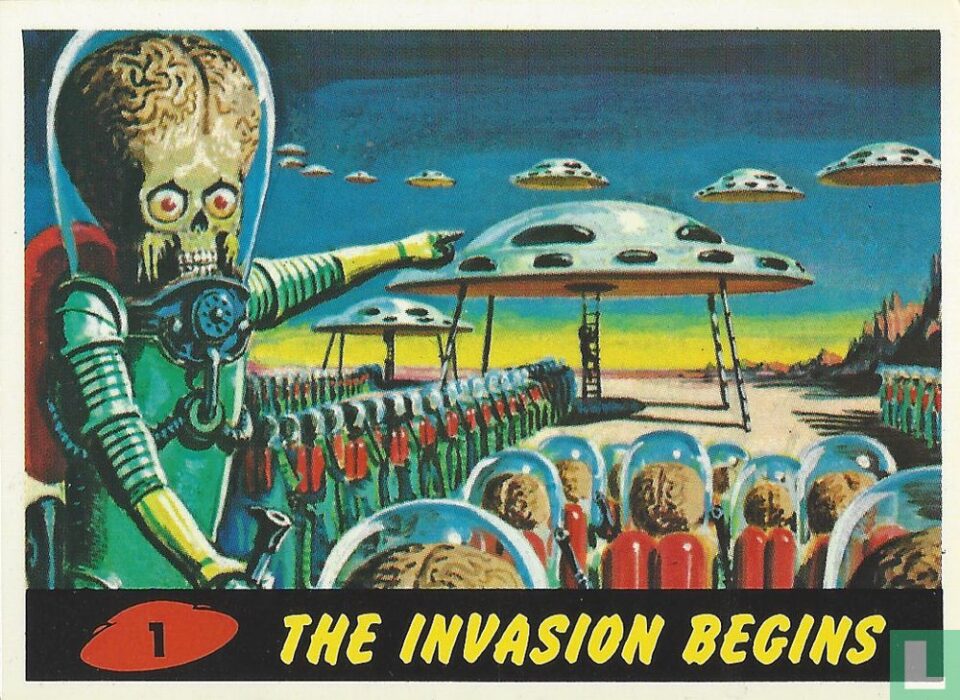

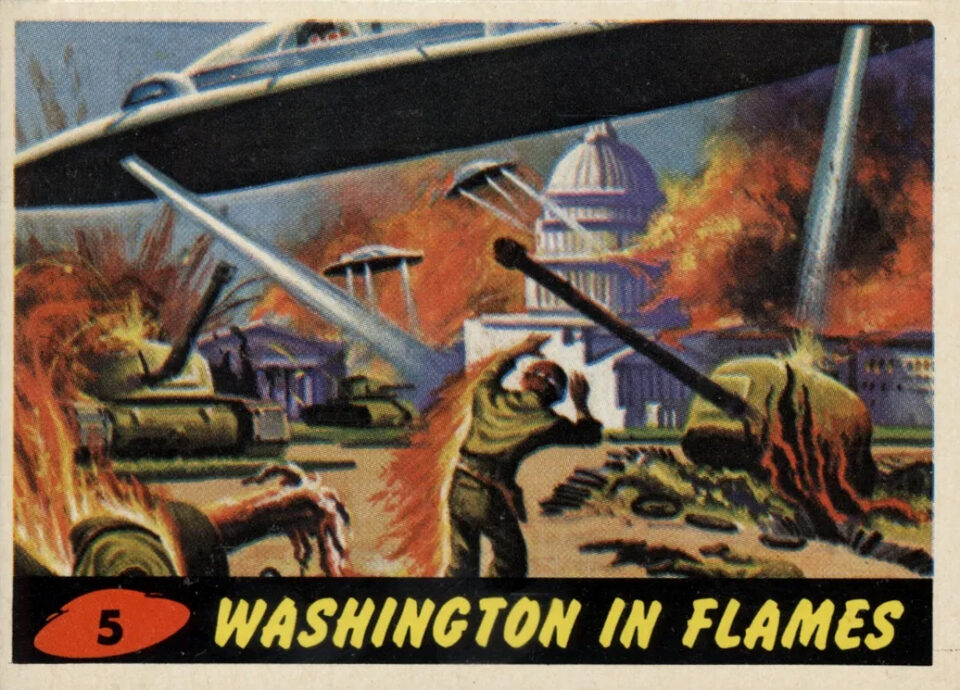

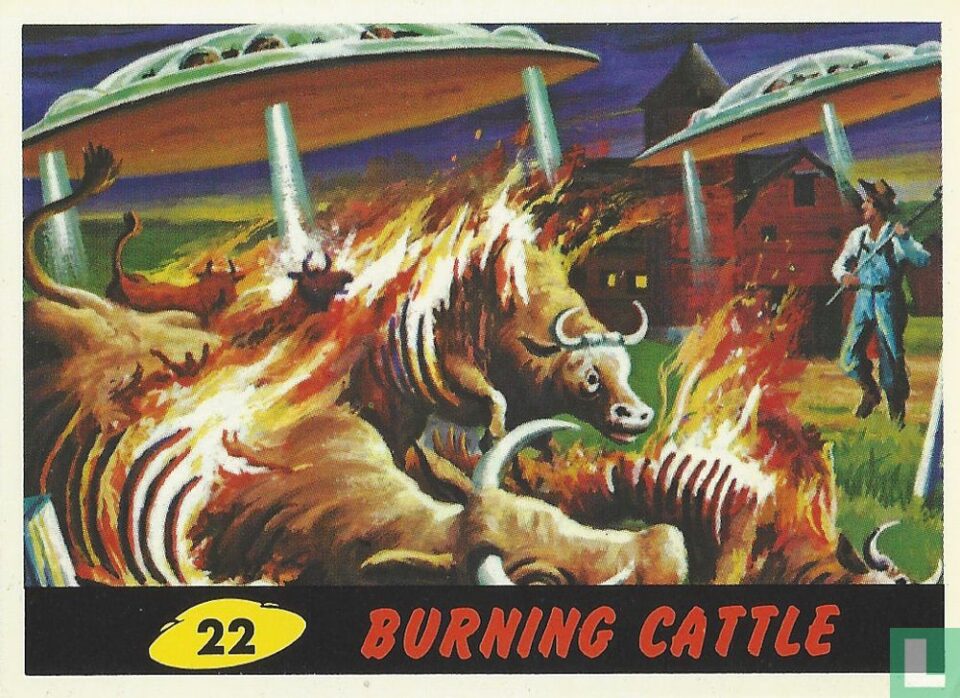

Tim est un grand fan de Ray Harryhausen, de Jason & les Argonautes et Des Soucoupes Volantes Attaquent. Cela a eu une grande influence sur sa carrière et c’était notre principale source d’inspiration pour Mars Attacks! Il voulait cette interaction entre de vrais acteurs et de la stop-motion dans un style de film muet de série B. Cela ne s’est pas passé comme prévu et c’est bien dommage, mais c’était quand même une super expérience et une façon pour nous de découvrir comment Tim Burton travaillait.

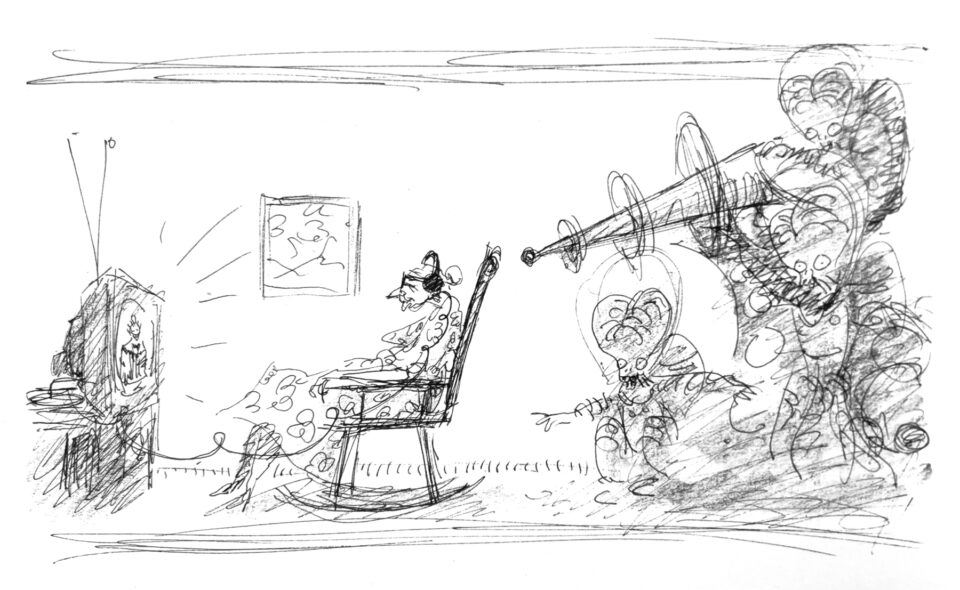

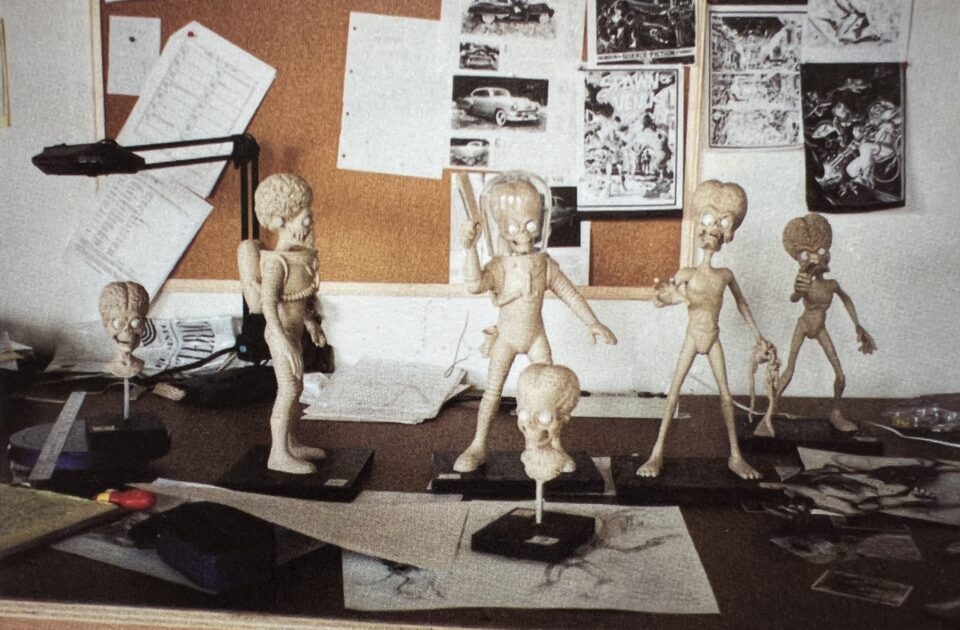

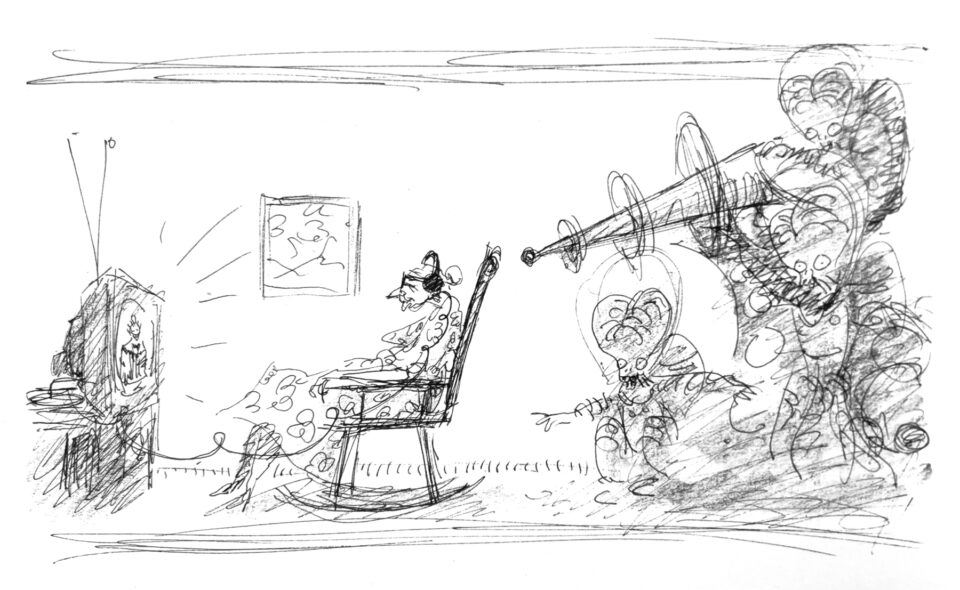

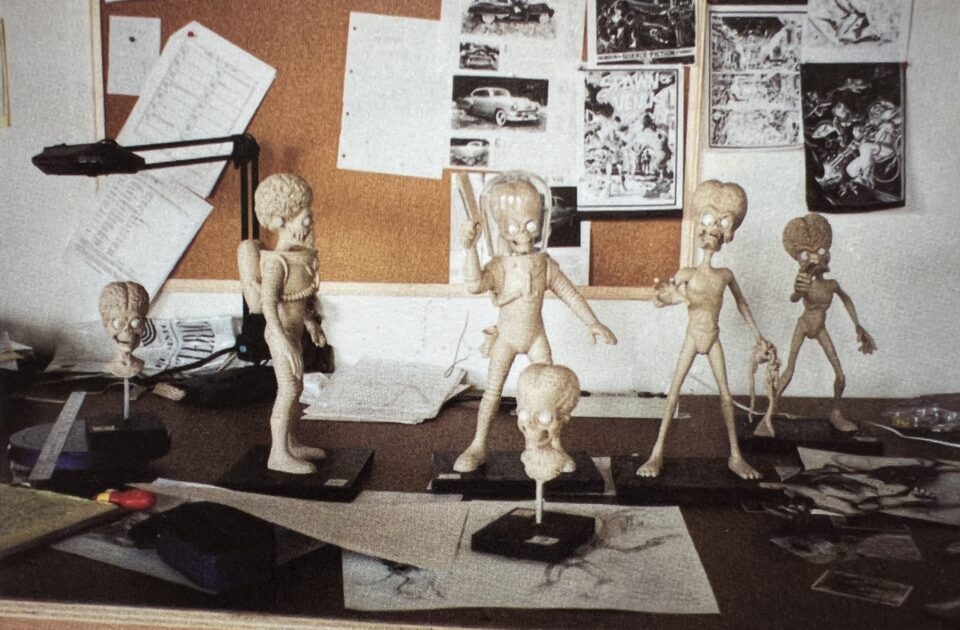

Tim a dessiné quelques croquis basés sur les illustrations des cartes à collectionner. Je travaillais alors avec des sculpteurs et de la plasticine pour donner vie à ses dessins et pour qu’il puisse voir à quoi ils ressemblaient en 3D. Ca l’a aidé et il est revenu avec d’autres croquis faits par-dessus des photos des sculptures. C’était comme un jeu de ping-pong ; j’envoyais des photos et il nous renvoyait des dessins. Comme c’est un grand artiste, quand il avait validé un design avec tous ses détails, je revenais toujours à ses premiers croquis pour vérifier que nous n’avions rien laissé de côté en chemin. C’est incroyable de se dire que quelqu’un qui réalise un film connaît également tous ces petits détails, jusqu’aux boutons de manchettes ou la forme d’une coiffure d’un personnage. Il a quelque chose de très précis en tête dès le début, et c’est ce qu’on verra sur la pellicule à la fin. C’est assez fascinant qu’un réalisateur ait une telle vision sur un univers complet. Bien sûr, il compte sur beaucoup de monde pour réaliser sa vision mais je pense qu’il y a peu de personnes qui ont autant le sens du détail que lui.

Nous sommes très fiers du travail que nous avons accompli car c’était un gros projet pour nous. J’ai déménagé à Los Angeles pour rejoindre les équipes créatives qui étaient dans le bâtiment à côté des Studios où était Tim Burton. Peter Saunders et les équipes de Londres produisaient les figurines, nous avons construit des soucoupes volantes et avions même commencé des tests d’animation au Studio. Mais le tournage des scènes live était trop lent pour nous livrer les images dont nous avions besoin pour travailler, donc au final c’était plus simple d’utiliser des images de synthèse. ILM a récupéré nos designs et s’en est servi de base pour leurs animations.

C’était une expérience incroyable et le début d’une collaboration de longue date avec Tim. Il sait s’entourer de groupes de personnes à qui il fait appel régulièrement pour de nouveaux films.

Quand nous travaillons encore sur Mars Attacks! à Los Angeles, Tim m’a montré quelques croquis qu’il a dessinés pour Les Noces Funèbres. Il avait déjà cette histoire en tête et voulait la développer. Une fois le tournage terminé, il a dit que nous allions faire un nouveau long-métrage en stop-motion après. Cela a pris 8 ans mais Tim est un homme de parole ! Même les dessins de Frankenweenie remontaient à ses années chez Disney. Dès qu’il le peut, il remet sur la table ses projets plus personnels. Il revisite ses personnages en faisant des croquis rapides comme avec Sparky. Personnage assez simple à première vue mais complexe à réaliser. Il dessine souvent des figurines difficiles à faire tenir debout, avec de longues jambes fines et des corps imposants.

Quand Tim est venu nous parler de Frankenweenie, nous lui avons demandé : “tu veux refaire un film live? Pourquoi revenir sur ces personnages ?” Je trouvais le premier court-métrage déjà très réussi. Il a répondu : “tout repose sur le chien et la performance de Sparky. C’est ce qu’il manque au court-métrage : le lien entre un garçon et son chien.” C’est ce qu’il espérait obtenir avec la stop-motion, la relation entre les deux, l’amour qu’a Victor pour Sparky et les conséquences dévastatrices de la perte d’un animal de compagnie. C’est, pour la plupart des enfants, leur premier rapport à la mort. C’était une manière intelligente de traiter un sujet sensible dans un film pour enfants.

Comment ton travail a-t-il évolué depuis les années 90? De la plasticine à l’animation mécanique en passant par l’impression 3D?

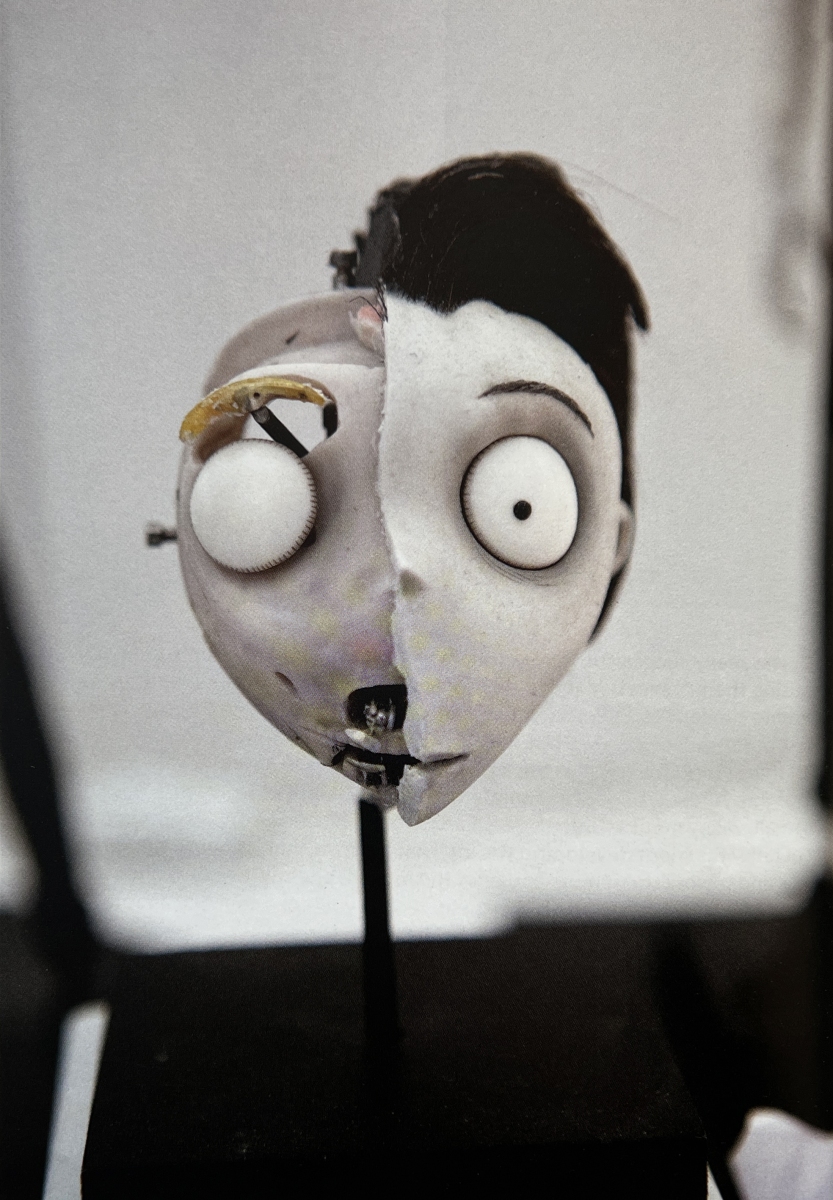

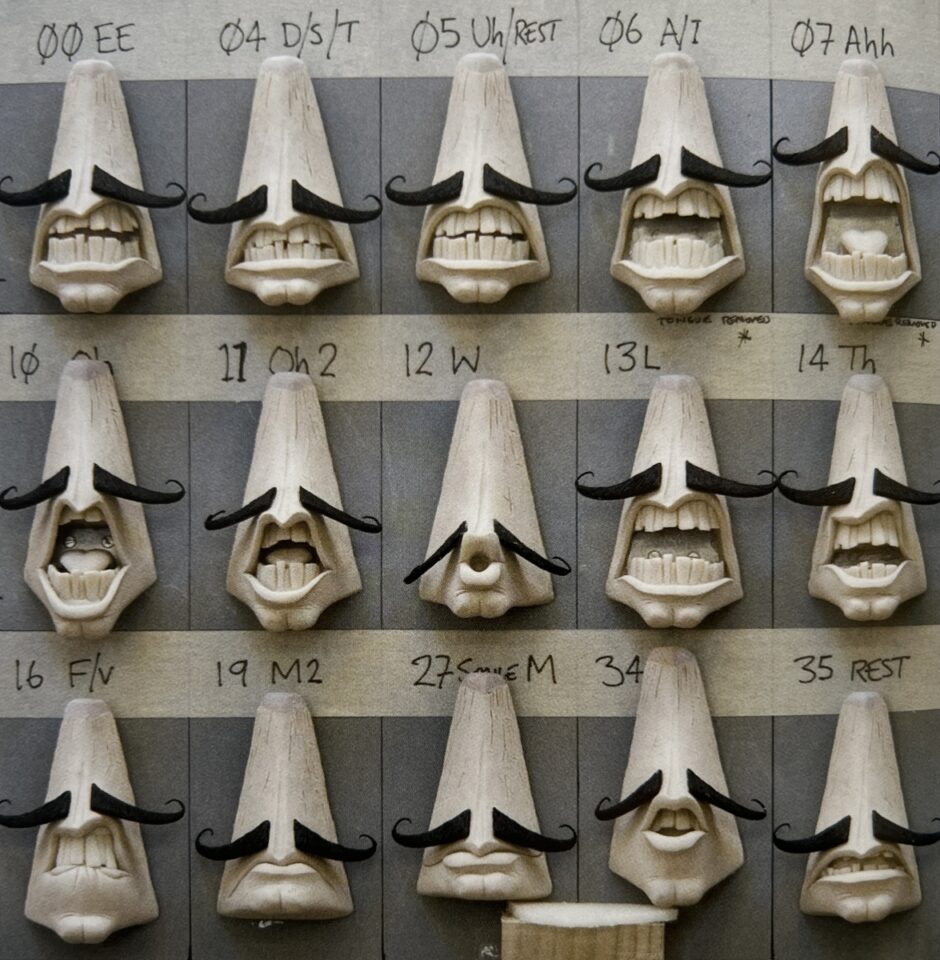

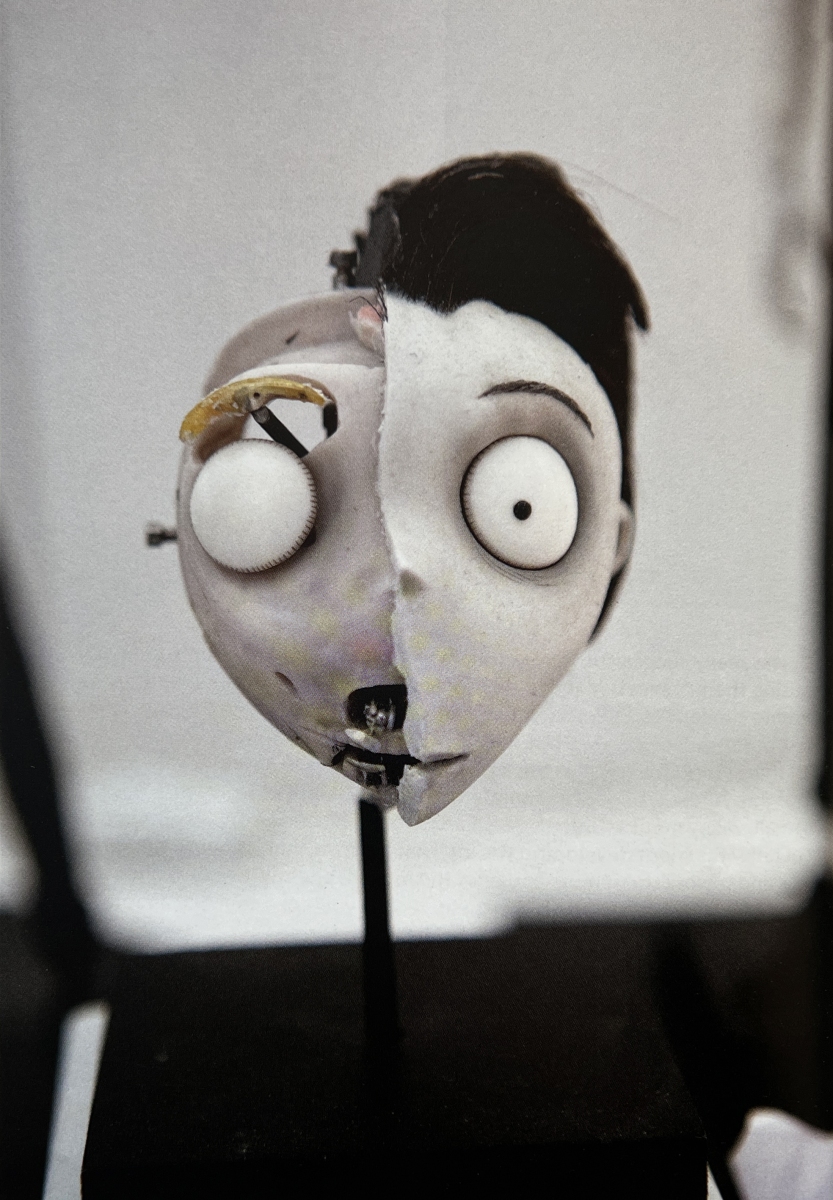

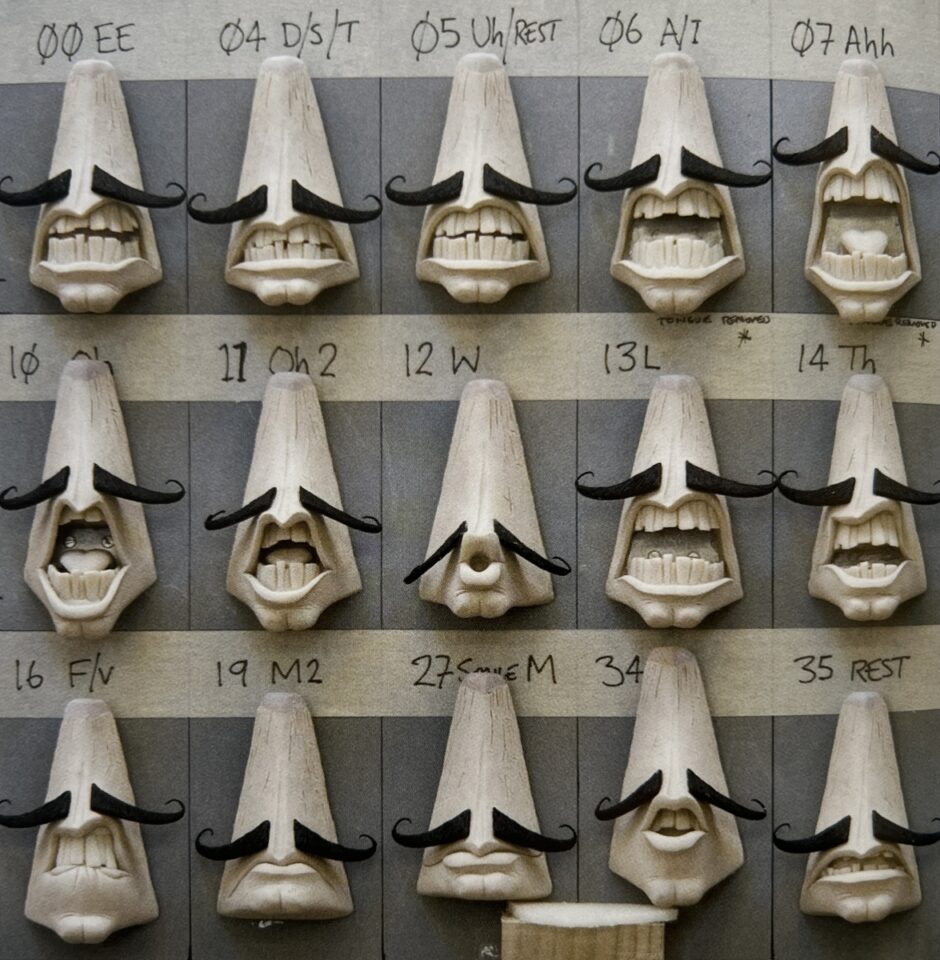

Pinocchio est un bon exemple hybride d’impression 3D et de têtes mécaniques. Mais nous avons vraiment commencé le développement de ces techniques avec Mike Johnson et Tim Burton sur Les Noces Funèbres (notre interview de Mike Johnson). A l’époque nous pensions utiliser la technique du remplacement de têtes comme pour L’Etrange Noël de Mr. Jack mais Mike voulait vraiment tester les têtes mécaniques. Il avait vu un de nos projets The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship pour lequel nous avions créé une tête mécanique et il voulait la même chose pour tous les personnages, ce qui représentait un vrai challenge pour nous.

Le vrai bénéfice de cette technique et pourquoi cela fonctionne sur la plupart des personnages est le fait qu’il donne à l’animateur la liberté de créer l’interprétation qu’il veut le jour même du tournage. Le réalisateur est là pour le diriger, il y a le storyboard et la bande-son de la voix enregistrée, mais l’animateur est seul maître de ses mouvements à ce moment précis. Ce que l’on voit à l’écran est entièrement dû au travail de l’animateur. A l’inverse, l’animation en impression 3D du visage de Pinocchio doit être faite par un autre animateur avant le tournage. C’est une autre technique d’animation et les deux ont leurs avantages. Nous ne pouvions pas réaliser toutes les expressions incroyables de Pinocchio avec une tête mécanique, donc l’impression 3D était la meilleure solution. Quelques personnages étaient un mix des deux. Par exemple, Spazzatura avait le haut de son visage en mécanique mais sa bouche était en impression 3D.

Sur Frankenweenie, Trey Thomas voulait également utiliser des têtes mécaniques. C’est un animateur extraordinaire et un réalisateur talentueux qui a animé Sally dans L’Etrange Noël de Mr. Jack. Nous avons peint les figurines en nuances de gris si bien que lorsqu’on arrivait sur le plateau de Frankenweenie, on avait l’impression de rentrer dans un monde en noir et blanc. L’environnement de l’animateur donne le ton du film. Et je pense que c’est ce qu’aime Tim Burton avec la stop-motion et les techniques traditionnelles. Plus vous avez de vrais décors sur le plateau, meilleure est l’atmosphère de travail pour le réalisateur, les animateurs et les acteurs. C’est tangible et c’est précisément ce que recherche Tim en ce moment : mettre la main à la pâte, retourner en studio et faire le plus possible les choses réellement. Nous avons toujours l’impression 3D et les images de synthèse qui viennent compléter l’animation en stop-motion, pas l’inverse.

Il y a 20 ou 30 ans, on nous avait dit que nous serions tous remplacés par le digital. Nous utilisons des caméras digitales mais il y a toujours un groupe d’irréductibles qui travaillent en stop-motion et cherchent à développer de nouvelles techniques pour l’améliorer. L’impression 3D est seulement un outil de plus dans notre boîte à outils. Nous voulons toujours que le résultat soit fait main. C’est important pour nous que le spectateur voit les marques et les empreintes de doigts sur les matières, ça fait partie de sa magie. Nous utilisons la technologie pour aller de l’avant, pour combiner les outils et, comme dans Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, pour faire d’une scène entre un Ver des Sables géant et de vrais acteurs, une expérience tangible. C’est peut-être une version miniature mais elle semble être bien présente à l’image avec les acteurs.

A quel point étiez-vous libre pour créer les séquences en stop-motion de Beetlejuice Beetlejuice?

Tim et les scénaristes ont réfléchi à comment réunir toute la famille de nouveau. Les funérailles de Charles étaient le prétexte parfait pour que toutes les générations de Deetz se retrouvent. Tim a fait un cauchemar une fois où il était dans un avion qui se crashait dans l’océan. Il a survécu mais a été croqué par un requin. C’était le point de départ de la mort de Charles. Nous savions que nous avions beaucoup de personnages à créer pour cette séquence en stop-motion, donc nous avons commencé à travailler dessus assez tôt.

Nous savions aussi que le Ver des Sables allait faire son grand retour, mais nous ne savions pas encore exactement comment. Il existe de nombreuses références grâce au premier film, donc nous avons cherché dans les anciens numéros de Cinefex des images de tournage et commencé à construire ses formes principales en plasticine. Nous avions 6 semaines pour tout shooter dans notre studio et ils avaient terminé les prises de vues réelles de la scène du mariage qui allaient nous servir de fond que très récemment. Nous avions déjà une prévisualisation de l’action et nous avons reçu les images de fond assez tardivement pour travailler mais nous avons pu tout finaliser. Notre directeur de la photographie, Malcolm Hadley devait s’aligner sur la lumière des prises de vues réelles. La scène sur la planète de sable a été séquencée plus tôt. Nous avons travaillé avec le superviseur des effets spéciaux Angus Bickerton sur l’intégration du Ver des Sables aux environnements en live action. Nous nous sommes demandé comment intégrer le sable ; nous pensions utiliser du vrai sable comme dans le premier film mais nous avons vite écarté cette idée. Nous avions plusieurs caméras témoins sur notre shoot en stop-motion. On enregistrait non seulement ce qu’on allait voir dans le film, mais aussi les côtés de l’action pour que les équipes d’effets spéciaux puissent calculer la longueur du Ver et avoir une meilleure intégration du sable. C’était aussi très utile pour les animateurs stop-motion, voir l’animation depuis le côté permettait d’avoir le bon rythme et une meilleure fluidité de mouvement.

Parce que le Ver des Sables était très imposant, son armature bougeait toute seule entre chaque prise. Anna Pearson, qui est animatrice dans notre studio, a trouvé la technique : elle utilisait une plume entre chaque prise pour lui toucher délicatement le nez et stopper son mouvement. Pour de la stop-motion, il était très difficile à animer à cause de sa taille.

Tu conçois des figurines et tu les animes en stop-motion, mais de temps en temps tu animes des figurines d’autres studios et inversement. Comment se passent ces collaborations?

Pour de nombreux projets, nous créons uniquement des personnages. Pour Pinocchio par exemple, nous avons créé quelques personnages principaux mais le collectif ShadowMachine et Georgina Hayns ont créé une centaine de figurines qu’ils ont animées dans leur Studio à Portland. Les Noces Funèbres et Frankenweenie ont tous les deux été tournés dans les Studios Three Mills à Londres. Allison Abbote y a constitué une super équipe d’animateurs. Notre rôle était de designer et fabriquer les personnages principaux qui étaient ensuite animés par d’autres équipes. Chaque mission est légèrement différente et notre rôle s’adapte en fonction du projet, de son ampleur et des équipes qui le constituent.

Tu as produit la vidéo promo de l’exposition de Tim Burton au MoMA en 2010 (exposition qui se termine à Londres en ce moment) et ton travail sur Pinocchio y était aussi exposé en 2023. Vos figurines réalisées pour Wes Anderson sont exposées en ce moment à Paris. Comment expliques-tu l’enthousiasme du public pour la stop-motion?

Quand j’étais jeune, nous n’avions pas accès à tout cela. J’aurais adoré visiter l’exposition de Tim Burton et voir des vidéos making of. Nous découvrons encore ce que nous pouvons faire avec le digital, surtout avec l’apparition de l’IA (comment l’utiliser? devons-nous l’utiliser ?). L’industrie du cinéma se repose parfois trop sur des images créées par ordinateur, si bien que le public ne sait plus où se trouve la réalité là-dedans. Ils préfèreraient en voir moins et ressentir plus. Le digital devient tellement irréel à des moments qu’il perd le spectateur. Je pense que c’est pour ça que Beetlejuice Beetlejuice a été un tel succès. Il comporte de très bons effets spéciaux mais il a aussi beaucoup d’effets pratiques. Si cela peut être fait sur le tournage, alors les acteurs et leurs performances semblent être plus réalistes et avec une énergie particulière. Tout commence par les croquis de Tim Burton. Voir tout cela à l’écran crée une continuité et le public le ressent.

Quelle est la différence entre créer un personnage pour Tim Burton et un autre réalisateur?

Tim Burton imagine souvent ses personnages des années auparavant. Ils ne sont pas juste dans sa tête, il les dessine régulièrement, même sur des serviettes de restaurants, et c’est ça qui est génial avec lui : il y a ses dessins, comment leur donner vie ensuite? Pour d’autres projets où le réalisateur ne dessine pas, il faut rassembler des références et des moodboards pour définir le style avant de commencer vraiment le travail. C’est une approche plus éparse au début, puis il faut trouver des designers qui puissent dessiner et enfin nous commençons à travailler en trois dimensions. C’est un processus légèrement différent.

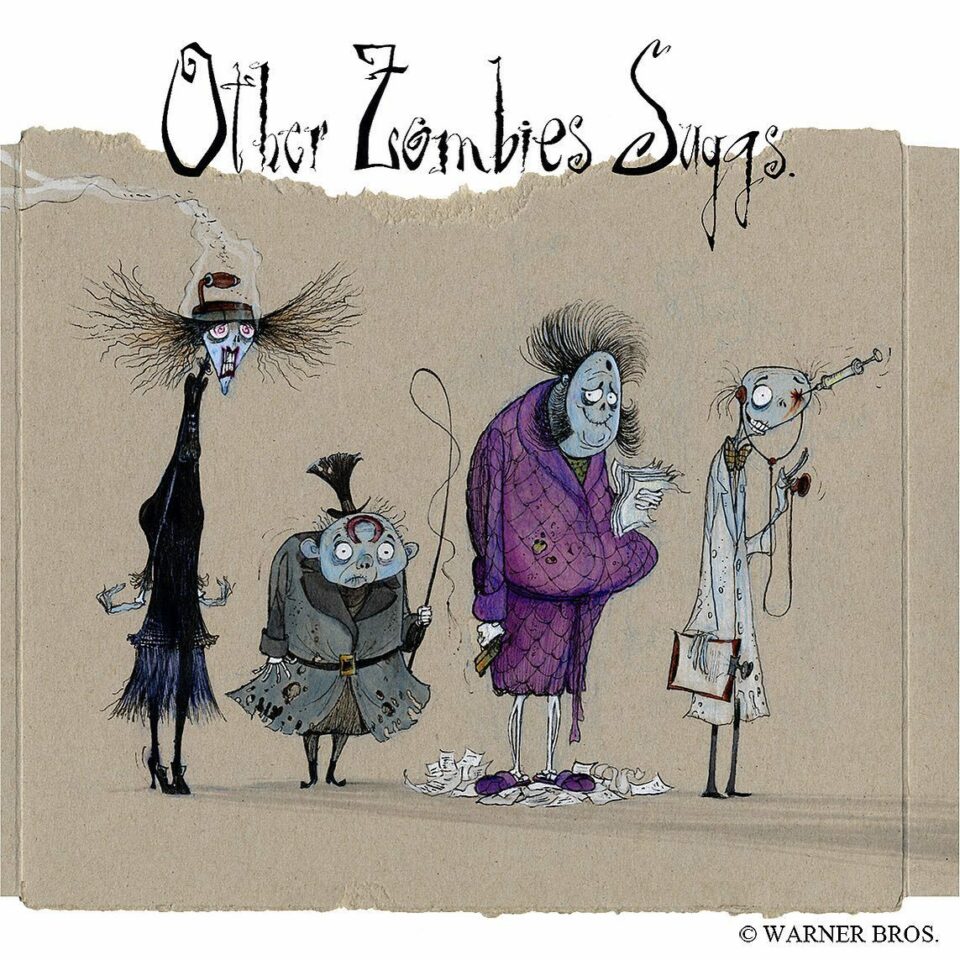

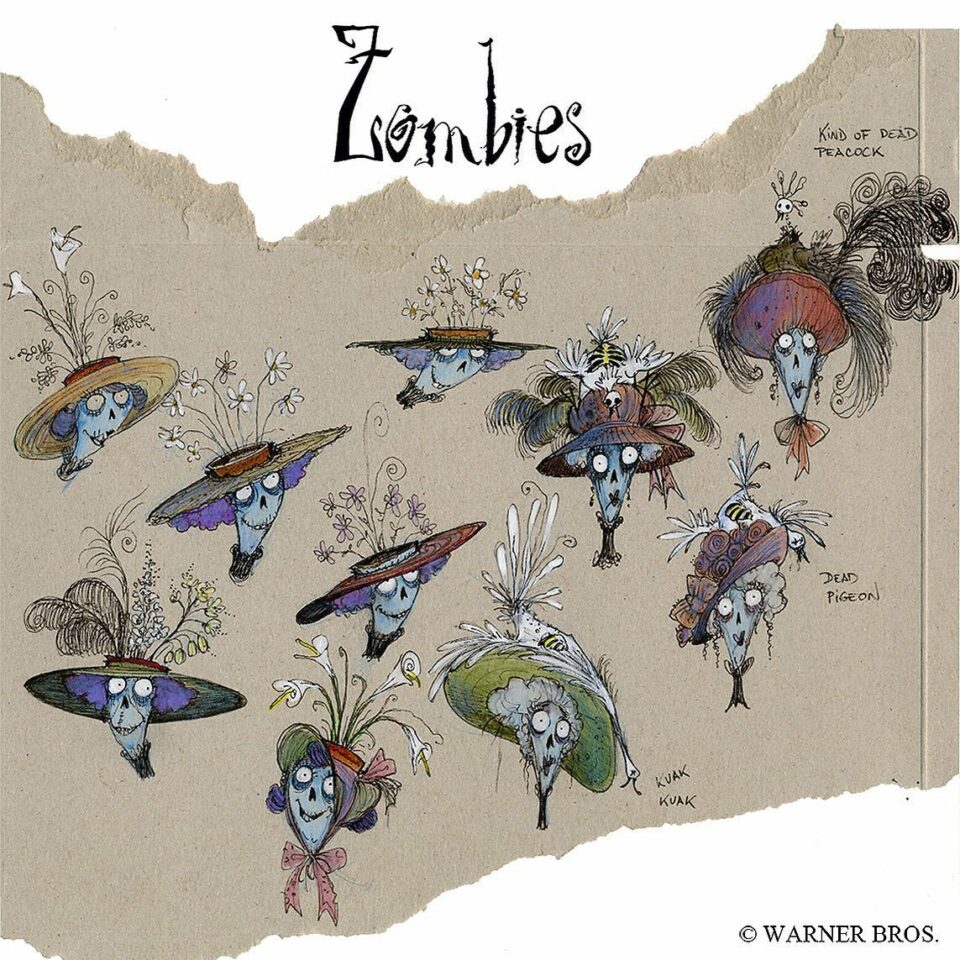

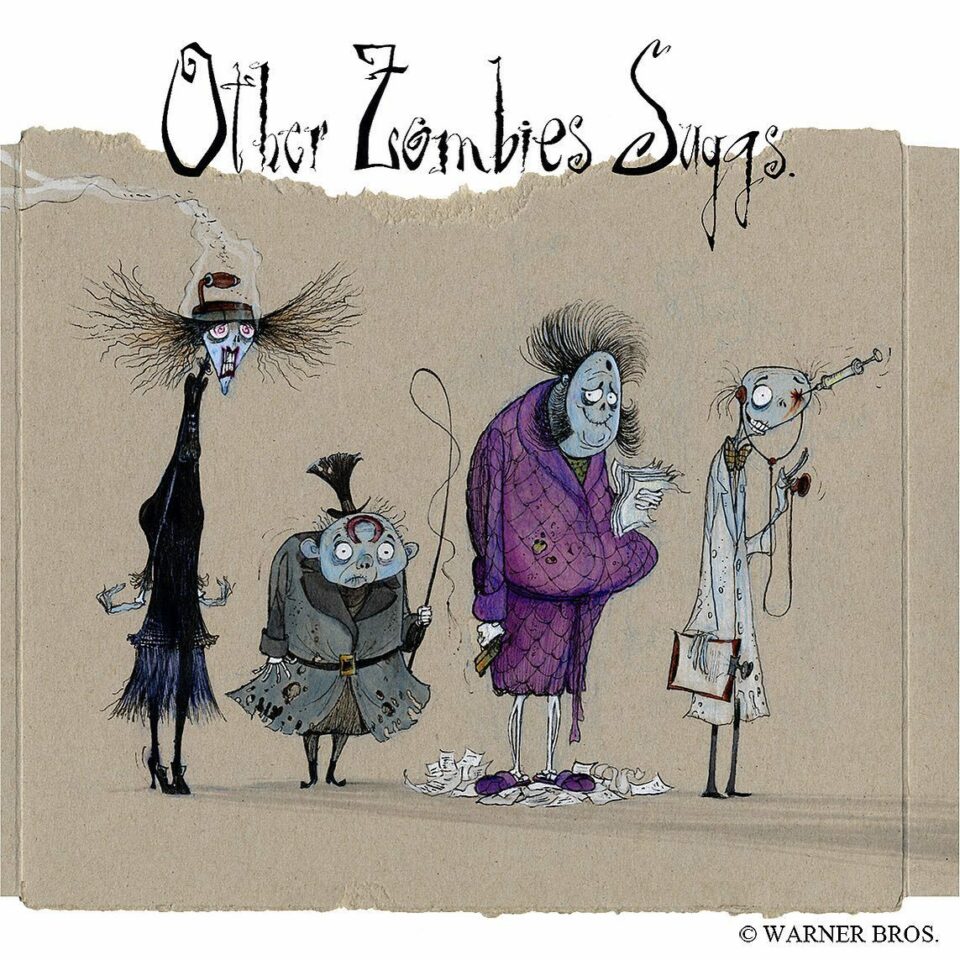

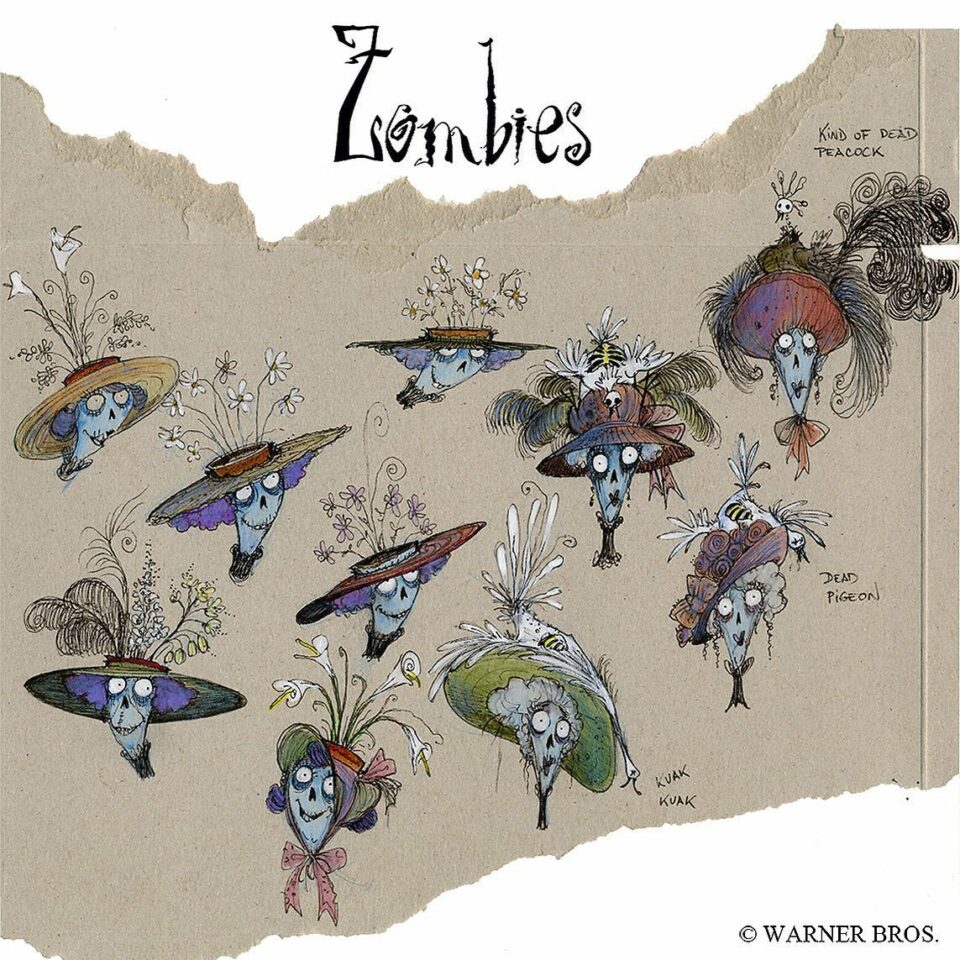

Pour Les Noces Funèbres, nous avons travaillé avec Carlos Grangel, un designer espagnol. Nous avons intégré Carlos à l’équipe car nous savions que Tim travaillait en même temps sur le tournage de Big Fish en Alabama. Tim a donné le ton et beaucoup de personnages principaux étaient déjà créés, mais nous avions un univers entier à remplir : le monde des vivants et le monde des morts. Nous avions déjà collaboré avec Carlos auparavant et nous pensions que son style allait bien fonctionner sur ce projet. Il a réalisé des centaines et des centaines de croquis qui étaient magnifiques. Tim avait alors la possibilité de dire : “j’aime ça sur ce personnage… je préfère cette couleur de costume… etc.” et nous pouvions ajuster au fur et à mesure.

Sur Frankenweenie, Tim avait fait énormément de dessins de Victor et Sparky. Il voulait qu’on commence directement à sculpter les personnages. Joe Holman, un de nos sculpteurs, a fait quelques croquis avec Tim puis nous avons travaillé très rapidement en trois dimensions pour montrer les formes à Tim et affiner au fur et à mesure. C’était en même temps que l’exposition de Tim Burton au MoMA donc nous avons pioché beaucoup de formes dans ses dessins, peintures et archives. Nous savions qu’il y aurait le papa et la maman à créer, mais il n’y avait aucun dessin d’eux. Comme nous connaissions déjà Victor, nous nous en sommes servis comme base pour les proportions de ses parents. Nous avons étudié les formes de personnages que Tim avait déjà dessinées auparavant pour nous inspirer. Nous en avons dégagé des formes grossières que nous avons affiné par la suite, jusqu’au plus petit détail. Cela permettait à Tim de redessiner par-dessus. C’était une technique très intéressante.

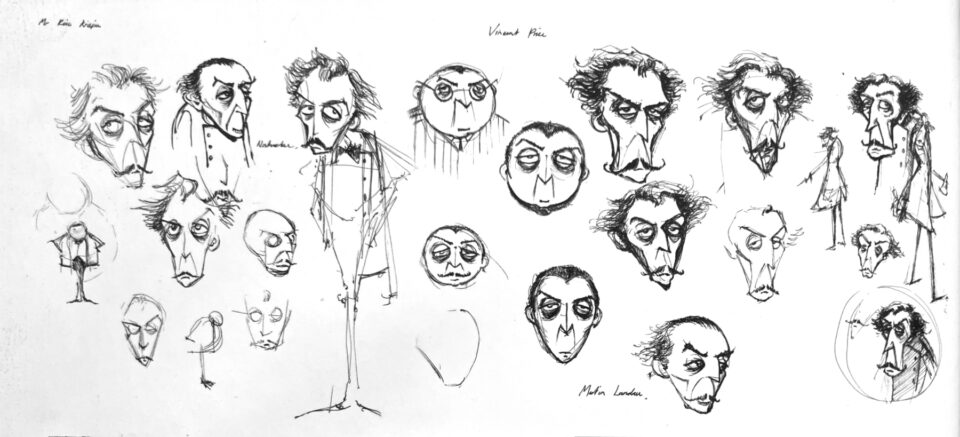

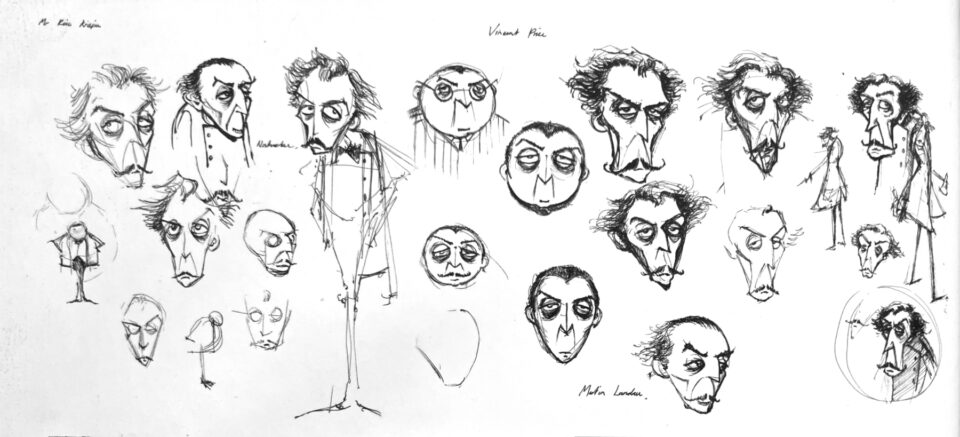

Parfois nous avions seulement le nom d’un personnage. Par exemple, nous savions que le Professeur Rzykruski avait un accent et un nom à consonance étrangère, mais c’était tout. Nous avons fait une série d’itérations en nous inspirant de Vincent Price que Joe a sculpté, et Tim a réagi à ces propositions. C’était un processus assez naturel. Nous avons pris le temps avec Tim de poser toutes les figurines sur la table de l’atelier pour qu’il puisse les regarder sous tous leurs angles, sortir son carnet de croquis, nous faire des retours et ainsi affiner le processus de création des personnages.

Quelle a été la figurine la plus fun à créer?

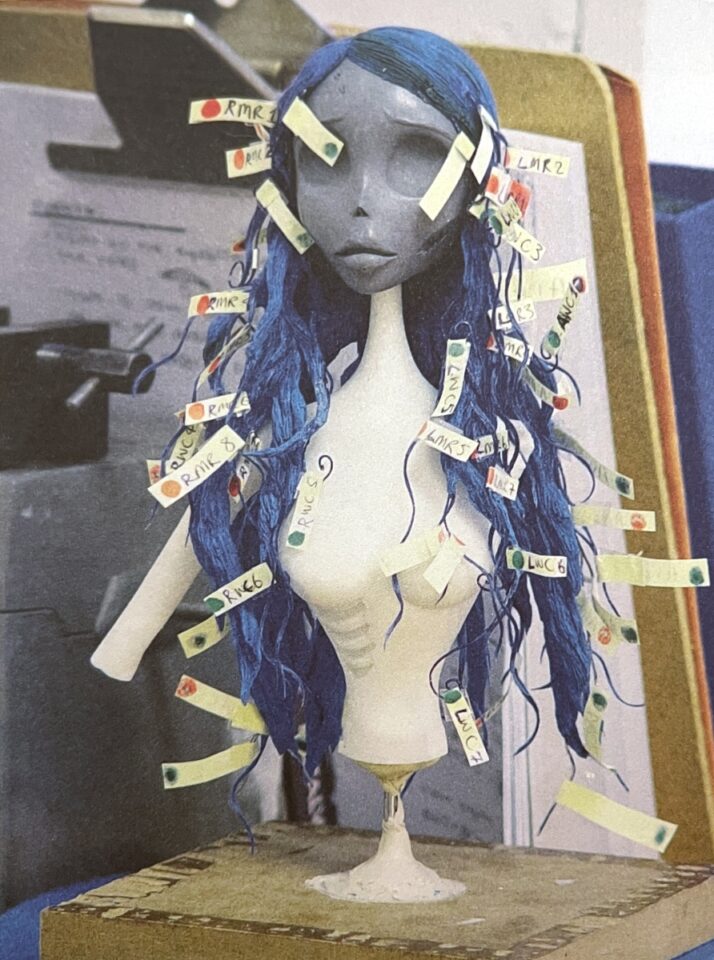

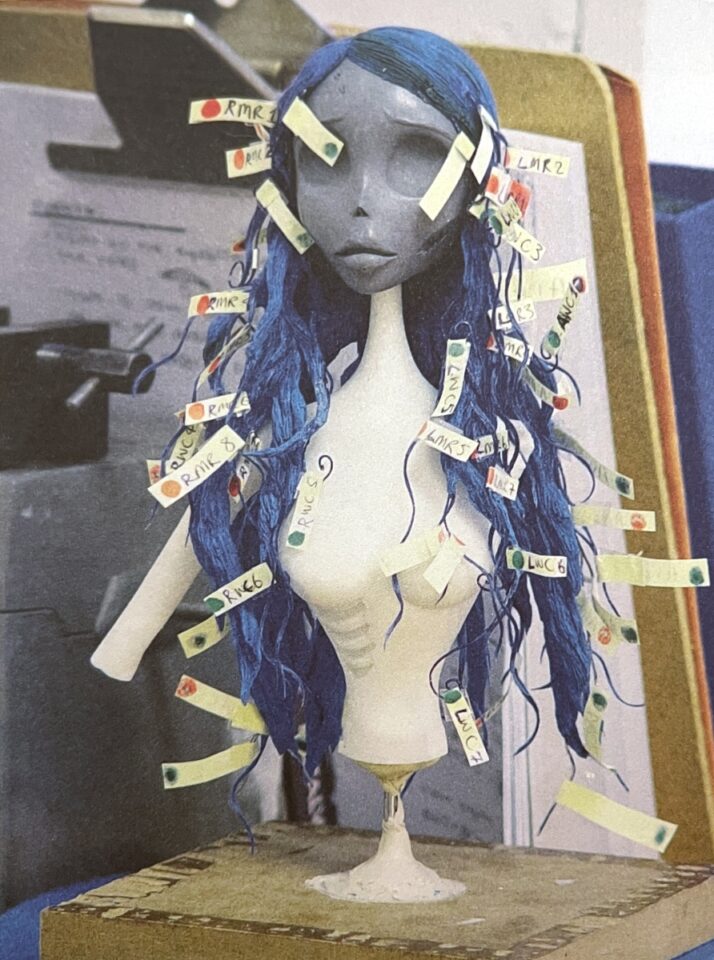

Je pense qu’Emily dans Les Noces Funèbres était l’une des figurines les plus complexes que nous avons jamais réalisées. Elle avait un voile, une longue robe de mariée, des cheveux longs, une jambe squelettique, un asticot dans son oreille… Il fallait 2 à 3 fois plus de temps pour l’animer que n’importe quelle autre figurine. Son design n’a jamais été validé à 100% d’ailleurs, nous faisions des ajustements jusqu’à la fin. Même quand sa figurine était fabriquée, il y avait constamment des choses à améliorer. Anthony Scott supervisait son animation. Une fois qu’elle était entre ses mains et que nous avons vu les premiers tests de marche, sa fluidité de mouvements et la beauté de l’animation de ses cheveux et de sa robe étaient notre vraie récompense. Nous essayons de donner aux animateurs tous les outils dont ils ont besoin pour donner vie au personnage, pour tester des choses et voir jusqu’où ils peuvent aller avant que la figurine se brise. Voir ce qu’ils arrivent à tirer de l’armature, jusqu’à quel point une matière inanimée peut devenir flexible et vivante, fait partie de la beauté de travailler en stop-motion.

Quel effet ça fait de créer des squelettes pour Les Noces Funèbres et de les montrer au grand Ray Harryhausen?

Mike Johnson avait organisé la visite de Ray Harryhausen dans les Studios. Je pense que nous étions tous un peu nerveux. C’était comme montrer nos devoirs au maître d’école. Il a été très généreux en commentant nos figurines. Je pense qu’il était vraiment ravi de voir un projet d’une telle ampleur avec autant d’animateurs passionnés. Aucun de nous n’aurait été là sans son influence. Il a ouvert la voie et c’était un vrai honneur de le rencontrer. Il a dit plusieurs fois que c’étaient les meilleurs squelettes qu’il ait jamais vus, avec une très belle armature. C’était très émouvant de lui faire visiter les Studios.

Je sais que Tim Burton et Johnny Depp ont visité sa maison. Même jusqu’à la fin de sa vie il partageait sa passion. Nous avons vu les archives qu’il avait dans son entrepôt de Londres et c’était incroyable ! Toutes les œuvres d’art qu’il a collectionnées pendant sa vie ! C’est magnifique que des personnes gardent leurs archives si précieusement, comme Tim le fait aussi avec ses dessins. Tout est si bien préservé. C’est peut-être qu’une serviette de restaurant mais avec un dessin dessus, cela devient un trésor inestimable.

Un immense merci à Ian pour nous avoir ouvert les portes de son atelier et partagé sa passion pour la stop-motion !

English Version

Ian Mackinnon is a producer in stop-motion animation. With Peter Saunders, they founded their Studio Mackinnon & Saunders in Manchester in the 90s. They create puppets and produce their own animations, working with renowned filmmakers such as Tim Burton (since Mars Attacks!), Wes Anderson (Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs) and Guillermo Del Toro for Pinocchio to name a few.

How and when did you discover the stop-motion animation?

I was always interested in puppetry and particularly in hand puppetry like Sesame Street and The Muppet Show. Growing up I was thinking that would be cool to be involved in. I was always aware of the stop-motion because we’ve have a heritage of producing stop-motion for children’s television in the UK. There’s a lot of shows I used to watch as a kid that used stop-motion: The Clangers, Trumpton, Camberwick Green…

I became aware of the work of Ray Harryhausen and seen his films, but the technique was a mystery to me. I could understand how Kermit was operated but there were very few books in our library, no Internet and no making of behind-the-scenes that you can look up for stop-motion, so it was a bit too far away for me. I had no idea how those things were made and didn’t realize that some of them were actually done 30 miles away in Manchester. Peter Saunders, my business partner, helped me get my very first job after school. I worked for Gerry Anderson, a TV producer who produced Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet. They were marionette puppets, incredibly adventurous shows. Working for Gerry Anderson brought me into the world of film prop making. So, when I returned to Manchester I started to work with Peter Saunders at the Cosgrove Hall Studios, producing stop-motion shows like The Wind in the Willows. I spent years in the studio learning, fortunately working from the bottom up developing my skills.

How do you split the work with Peter Saunders?

We are still puppet makers, but we are also producers now. I tend to spend more time on the sculpt and design side, trying to oversee what the director and the producers wants for the look of their characters. Peter is coming from a background of armature and engineering work. He developed a very unique system of head mechanics. He started with Jim Henson on the live action film Dark Crystal. He worked on how to miniaturize and shrink all of the animatronics techniques and then implemented some of them in the stop-motion process. That’s how we split the work but over the years, we build a company together and we’ve got into production work as well. We produced children TV series, commercials, short films and recently all the stop-motion animations for Beetlejuice Beetlejuice in our studio. We wear all different hats.

How was your first collaboration with Tim Burton back in 1996? How did it evolve?

Tim is a huge fan of Ray Harryhausen, Jason & the Argonauts and Earth vs. The Flying Saucers. It has a great influence on his filmmaking, and it was a key reference for Mars Attacks! Tim wanted that interaction between stop-motion and live action in a B-movie style. It didn’t go according to plan. It was a shame but it was still a great experience for us and an introduction to Tim Burton’s way of working.

Tim drew some sketches inspired by the Topps trading cards illustrations. I was working with the design sculptors to flesh things out with plasticine so he can see how it looks in 3D. It helped him and he came back with more sketches done over photographs of the sculpts. It was like a game of tennis; we send something over and he send something back. Because he is such an amazing artist, once he’s decided on the final look of a character with all its details, it’s always great to come back to these early sketches to make sure we didn’t lose any details or the energy of his drawings. It’s incredible to think that someone who’s directing the movie also know all its details, down to a button or the shape of someone’s hairstyle. He has something locked in his mind that eventually will be seen on the screen. For a director to have that overview of an entire visual world is quite fascinating for me. He obviously relies on lots of people to help with that process but I think there are very few people that have quite that amazing eye for detail.

We are really proud of the work and the design we did as it was a big project for us. I moved to Los Angeles and joined the design Team in the building next to the Studio where Tim was. Peter Saunders and the Team in Manchester were working on the manufacture of the puppets. Flying saucers were built and we even started some tests in the LA studio. But the scheduling of the live action shooting didn’t happen quick enough to give us the background plates that we needed so it was easier to use CG at the end. ILM took our designs and use it as a base for the characters.

It was an incredible experience and a great introduction for our collaboration with Tim that is still ongoing. Tim seems to surround himself with groups of people that he comes back to on many of his films.

When we worked on Mars Attacks! in LA, Tim showed me some of the drawings he’s done for Corpse Bride. He had already that story in his mind and wanted to develop it. When Mars Attacks! was finished, he said that we’ll do a full stop-motion film next. It took 8 years but he’s a man of his word. Even for Frankenweenie‘s drawings, the originals go back to when Tim was working in Disney’s Studios. When he can, he tries to push his more personal projects along. He revisits those characters, doing very quick sketches like Sparky. A quite simple looking character but not easy to build. Often what he draws are rather difficult puppets to make, with tiny legs and big round dumpy bodies.

When Tim came to talk about Frankenweenie, we asked him: “Why do you want to go back to revisit those characters?” Because I thought the first live action film was fantastic. He said: “it’s all about the dog and the performance of Sparky. That’s what is missing from the film, the connection between the boy and his dog.” That’s what he was hoping to get with stop-motion animation, the relationship between the two of them, the love that Victor has for Sparky and the devastating consequence of losing a pet. Which for many children, is the first experience of loss and grief. It was a clever way of dealing with a sensitive issue for a young audience.

How did your work evolve since the 90s’? From plasticine to 3D printing and mechanical animation?

Pinocchio is a really good example of combining 3D printing and mechanical heads. But we started to develop it while working with Mike Johnson and Tim Burton on Corpse Bride (our interview with Mike Johnson). We had discussions early on with Corpse Bride about using face replacements like in The Nightmare Before Christmas, but Mike Johnson was really keen on using mechanical heads. He’d seen one of our projects The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship where we made one mechanical head and he said he wanted that look for every puppet, which was quite a challenge for us.

The benefit of that and the reason why it works for most of the characters is that it gives the animator the ability to create the performance on the set, on the day. The director will be directing them, they’ll have the storyboard and the voice track, but the animator creates the full performance alone on the set with the puppets. What you see on the film at the end of the day is their performance. Whereas with Pinocchio, the animation of the 3D printed faces of Pinocchio puppet must be created by another animator before the studio shooting. It’s a different process and both have their benefits. We couldn’t get Pinocchio’s face to do all the incredible work it does using mechanics, so 3D printing was a really obvious choice to make. Then few of the puppets we made were a mix. Spazzatura has a replacement mouth but a mechanical brow.

On Frankenweenie, animation director Trey Thomas wanted to use mechanical heads too. He animated Sally in The Nightmare Before Christmas and he’s an incredible animator and a fantastic director. We painted the puppets in monochromatic shades so when you walk in the Frankenweenie studio, you felt you were already in a black and white world. The environment of the animator sets the tone to the film. And I think that what’s Tim like about the process of stop-motion and traditional camera techniques. The more you can have on set the better the environment and atmosphere for the director, the animators and the actors. There’s a real tangibility to it and I think that’s what he’s keener on doing now: get your hands dirty, get back in the studio to do things in a more practical way whenever it’s possible. We do have 3D printing now; we do have CG and amazing digital work, fantastic tools that we can combine with stop-motion.

We’d be told 20-30 years ago that we’ll be extinct very soon, that digital will replace everything. We shoot the animation on digital cameras but there’s still a vibrant band of people working in stop-motion trying to develop the techniques and improve what we do with each film project. 3D printing is just part of our toolbox now. We still want things to feel like they’re handmade. It’s really important for us that the audience see the marks and the fingerprints in the surface, that’s part of the magic of it. We use technology to keep pushing things forward, to combine the techniques and hopefully, like for Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, making a stop-motion sandworm among live action characters is a believable experience. It might be a miniature version, but it feels like it’s actually there in the studio with the actors.

How free were you to create the stop-motion sequences in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice?

Tim and the writers thought of how to bring the family back together once again. The funeral of Charles was a great way to put all the generations of Deetz together. Tim had a nightmare once where he was on an airplane and crashed into the sea but survived. He didn’t drown, but a shark bit him. So that was sort of the set out for Charles’ death. We knew we have to create lots of stop-motion characters for that sequence on the doomed airplane. We started to work on the design quite early on.

We knew that the Sandworm was going to make a comeback, but we didn’t know what it will really do at that stage. However we had lots of existing references from the first movie and we would look back through all of the Cinefex magazines, finding some stills so we could start blocking out the Sandworm sculpture with plasticine. We had 6 weeks of shooting to capture everything in our Studio, they had recently finishing filming the wedding sequence in live action to create the background plates for our stop motion animation. We had a rough animatic early on and we got the background plates quite late to work with but we were able to line these up. Our director of photography Malcolm Hadley had to match the lighting from the live action too. The sequence on the sand planet had been blocked out much earlier on. We worked with the VFX supervisor Angus Bickerton on the development and how to combine the Sandworm into that live action environment. We discussed about the interaction of the sand, about using live action sand again like in the first movie but that idea was dropped pretty quickly. We had witness cameras on our stop-motion shoot so not only we shoot what you see in the film, but the side of the animation too. Seeing the depth of the puppet helped the CG sand interaction. It was really helpful for the stop-motion animators as well, to see the animation from the side and help get the right flow for the movement.

Because the Sandworm is quite big, it gets a bit of recoil in between the frames and the weight of the armature give a little bit of movement. Anna Pearson, who’s one of the animators in the studio, discovered a technique: using a feather, she could gently touch the nose of the Sandworm with it and stop the rocking. It was a beast to animate because he’s quite a big puppet for the stop-motion world.

You create puppets and produce animation. Sometimes you animate puppets from other Studios and vice versa. How those collaborations work?

For a lot of projects, we create only characters. For Pinocchio, we created some of the lead characters, but ShadowMachine and Georgina Hayns did hundreds of puppets as well and the film was shot in their Studio in Portland. Corpse Bride and Frankenweenie were both shot in Three Mills Studios in London. Allison Abbate put an amazing crew and a team of animators together. Our role was to design and build the lead characters that will be animated by another team. Every job is set up slightly differently and our role changes depending on what the project is, its scale and who will work on it.

You produced the promo movie of Tim Burton’s exhibition in MoMA in 2010 (which is still running in London right now) and presented your work from Pinocchio in NY as well in 2023. How do you explain the public enthusiasm for stop-motion?

We didn’t have access to any of that when I was growing up. I would have loved to visit the Tim Burton exhibition or see a making of video. We are still discovering what we can do digitally, moving to a world where we think of AI – how to use it? do we use it? The film industry uses digital so extensively that sometimes the audiance asks where’s the reality in it. They’d rather see a little bit less and feel a little bit more. Digital sometimes become so unreal that it can lose the audience. That’s why I think Beetlejuice Beetlejuice was so successful. It has great digital work, but lots of practical stuff too. If it can be done on the set, then the actors and the performances are more down to earth with a qualitative energy to it. It all starts in Tim sketches. Seeing everything on the screen at the end, creates a connection through start to finish and the audience respond really well to it.

What’s the difference between designing a puppet for Tim Burton and other filmmakers?

Sometimes Tim Burton imagines his characters years before. They’re not just in his head, he draws them many times, even on napkins in restaurants, and that’s the really great thing about working with him: there’re the drawings, how do we bring them to life? For another project working with another director who doesn’t sketch, you probably had to put together references materials to start with, to define the style etc. It’s more a scattered approach to start with, then you bring some designers on board who can sketch and then you start working in three dimensions. It’s a slightly different process.

On Corpse Bride we worked with a Spanish designer Carlos Grangel. We brought Carlos on board because we knew that Tim was going to be really busy working on Big Fish in Alabama. Tim had already set a style and lots of the lead characters were fleshed out but we had an entire world to fill: both land of the living and land of the dead. We worked with Carlos before and we thought his style would match. He did hundreds and hundreds of sketches which were absolutely beautiful. That gave Tim the opportunity to say: “I like this about this character… I prefer that costume… etc” Then we could adjust step by step.

On Frankenweenie, Tim did a lot of sketches of Victor and Sparky early on. He wanted us to explore directly with sculptures. Joe Holman, one of our sculptors who also does sketches, did some early drawings with Tim then we tried to work in 3 dimensions as quickly as possible to give those shapes to Tim to look at and refine them. It was at the same time as the MoMA exhibition. So, we borrowed lots of shapes from his artworks, drawings and archives. We knew there was a Mom and Dad but there were no real sketches of them. As we knew what Victor looks like, we use it as a base for the shape, size and scale of Mom and Dad. We looked at some of Tim’s character’s shapes he had drawn before and use that as an influence. We started blocking things out, as a very broad proportional 3D sketches, then we started to develop them and get into more details. That allows Tim to sketch over the top of those models. That was a really interesting process.

Sometimes we had just a name of a character. For instance, we knew that Professor Rzykruski had a foreign sounding name and a foreign accent but that was it. We did a couple of variations with a slightly Vincent Price influence that Joe sculpted, and Tim responded to that. It was quite an organic process, taking the time with Tim in the workshop, put all the puppets on the table so he can sit and look at them, turning them around, get his sketchbook out and help refine the process of the character development.

What was the puppet you had the most fun to create?

I think Emily in Corpse Bride is one of the most challenging puppets that we have done. She has the veil, the wedding dress, the hair, the boney leg, the maggot coming out of her head… She took 2-3 times longer to animate than any other character. And we never got the design approved, we were always making slight modifications to her right until she was on set. Even when we sculpted it and making the puppet, there were constantly things that had to be refined. Anthony Scott was supervising the animation of Emily. Once you give it to the animators and you see the character walk for the first time, the flow and the beautiful movement of the hair and dress is our reward. We try to give the animators all the tools they need to do that performance, letting them try things and see how far you can push it before it breaks. Seeing how much they can get out of the model, how much flexibility can they get from inanimate materials, is all part of the beauty working with puppets.

How did it feel to create skeletons for Corpse Bride and show them to the great Ray Harryhausen?

Mike Johnson had organized the visit of Ray Harryhausen in the Studio. I think we were all quite nervous. It was like showing your homework to the master. He was very generous with his comments about the puppets. I think he was just thrilled to see a project of that scale, with so many animators working at that level. None of us would be there without his influence. He paved the way. It was really an honour to meet him. He did say: “it’s the finest skeletons I’ve ever seen! With the finest armatures” I think he said that several times. It was a real thrill to get him into the Studio.

I know that Tim Burton and Johnny Depp went to his house. He was still doing talks until quite later on his life. We saw the archive that he had in his warehouse in London and it was amazing ! All the Art he collected over the years ! It’s wonderful that people do keep their archives in such beautiful manners, like Tim does as well, the most incredible archive of his artwork. Everything is so beautifully kept. It might be a napkin but with a sketch on it’s a treasured possession.

We are so grateful that Ian opened his Studio to us and shared his love for stop-motion animation !